For those who grew up in a Communist nation, one affiliated with the Warsaw Pact and the International Communist Movement, attaining feelings of “freedom” might have been hard to come by for those with artistic inclinations. Russians (or Soviets) were and are well-known for their abilities in academics and engineering, as well as sports. There is a very clever reason for this: these were fields in which they were free to exercise the natural human desire to be creative, use one’s talents to perhaps make the world a better place. Even under the worst conditions created by Stalin and ensuing leaders, Soviet citizens were considered to have performed well in the aforementioned fields. Medicine was also considered another excellent career path and doctors graduated at a younger age than in the West because academics were pushed to the forefront of daily and social life. It was a matter of national pride.

In Mainland China, there exists such a place for breeding future artists— but not many have known about it until recently. Exuding a cool Cold War vibe via its background and modern rebirth,the area is now known as the “798 Art Zone.”

Make no mistake: this industrial area has interesting origins. Known as the “Dashanzi Factory Complex,” it was formerly a cooperative engagement founded upon an alliance with the erstwhile Soviet Union (and East Germany). This was preceding an era in which many were told, and believed, that there was a Sino-Soviet split.

I happened upon 798 when I had a spare day in Beijing after a trip to North Korea. My desire to see the area had been piqued by positive reports from my clients who had taken art tours here with one of our art experts. In the back of my mind, of course, as it always is, was the thought that it would be a productive photographic outing. I quickly discovered that due to the sheer immensity of the area, it’s best to have an idea where you want to go instead of just walking around aimlessly.

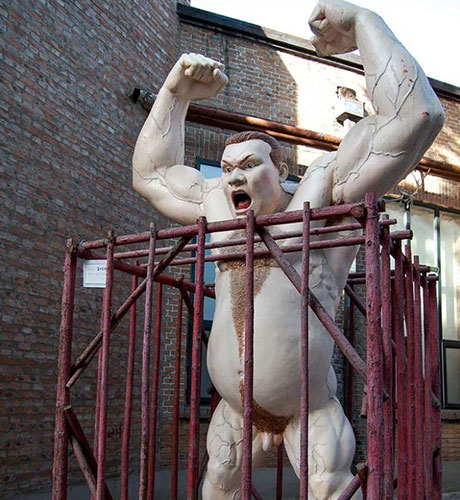

There are some amazing displays of contemporary Chinese art — from the enormous graffiti displays, quirky exhibits that have sprung up in places where you might not expect, to galleries holding exhibitions of local artists. The art on display is quite impressive and provides an informative crash course in modern Chinese art.

The factory complex called 798 was a part of the Socialist Unification plan. Soviet and German architects and engineers sparred over how the complex should be designed. The Germans wanted a great deal of natural light and to accentuate their Bauhaus form of architecture. The Chinese, ever mindful of Feng Shui, had their own ideas. The factory complex was designed to be earthquake-proof and cost nearly US$ 20 million to build. Materials were brought in on the Trans-Siberian railway system. The People’s Liberation Army felt the complex strategic and vital, as they were importing what were then considered sophisticated electronic components from East Germany (that project was called 157). The construction of the 798 complex began in 1954 under the watchful eye of dozens and dozens of German experts.

By 1995, the Chinese government saw the potential of the complex as an art-based cooperative. In the ensuing years, various Westerners and other foreigners migrated to the enclave to set up their own commercial and artistic endeavors. Ultimately for the Chinese government, 798 serves two important functions: first, it shows off the idea, if not practice, of “freedom” through art, and second, it keeps the “freedom-oriented” types corralled together in one special area where it might be easier to assess (and keep an eye on) their activities. But the Chinese are extremely patriotic, always keen to show off their technology, even wishing to build a colony on the moon and in the most general terms continue their climb towards a top world power. Artists won’t get in the way of that zeitgeist.

In terms of appropriations and artistic practice, you could not ask for a more diverse enclave. Not far away from 798 lives the man who designed China’s main Olympic Stadium. When it comes to art in China, it would seem the sky’s the limit at 798. As for any ancillary impact that such works of art might have in the culture, that chapter has yet to be written … or painted … or sculpted … or filmed … or turned into performance art. Artists, like journalists, are meant to encourage a society to question itself and then offer possible solutions to tough issues. Art, at times, can transcend the traditional boundaries of the very definition of the word “art.” It can provide a context and pretext to social trauma that might otherwise be ignored or go unaddressed. 798 provides an opportunity to fill such a void, if it indeed exists.

Who could have suspected such an ending to the complex’s militaristic beginnings? I can imagine Chairman Mao turning in his grave when he sees what’s become of 798. Or perhaps even he would agree that a little revolution now and then is a good thing — don’t you think?