Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius once said, “Death smiles at us all … all we can do is smile back.” Truer words were never spoken in relation to Torajaland, a unique outpost amid Indonesia’s thousands of islands. Torajaland stands out as a fascinating place for overseas adventure enthusiasts, for many reasons. There’s the unique Torajan architecture, the fact that inhabitants are former headhunters, and the tumultuous history and conflict with the Dutch, who attempted to conquer the area, and were only able to do so by spreading Christianity. Torajaland is also famous for being a region where outstanding coffee is produced. And finally, there is the aspect for which the Torajans are the most famous, the elaborate rituals associated with death.

Signs of death can be seen everywhere in Toraja. Every cave and ditch is likely to have coffins or bones scattered about. Humans in every culture throughout history have had questions about life after death. Few cultures, however, invest so much emotionally, spiritually, physically and socially in such metaphysical questions as do the Toraja. These are a people with no written language. Instead, they carve symbols into wood, in a form ofinformation packaging known as “Pa’ssura.”

Torajaland is a place unlike any other, both for its unique culture and its stunning landscapes. Getting there can be a major challenge, with only two choices: flying into Sulawesi’s largest city, Makassar, and driving six hours, or chartering a private turbo prop. There was once a commercial flight between Makassar and Rantepao, but that route was canceled and hasn’t operated for a few years.

The aura of mystery surrounding this area is interesting and complex,intertwining the forces of history, religion, geography and culture. The Toraja have made their homes in the highlands of Sulawesi, and number about 650,000 in total. Many of them, or even most, are Christians, having been converted by Dutch missionaries. The Dutch arrived in the 1600’s and established what would be a long history in Indonesia – mainly through the Dutch East India Company. The Dutch, concerned with the rise of Islam, saw the animist elements of the Toraja as making them “suitable for conversion to Christianity”.

At first only 10 percent of the Toraja converted to Christianity, but during the Great Depression in the West during the 1930’s, Islamic believers attacked the Toraja. This is not a well-known fact. By the 1950’s , due to these attacks and persecution, masses of the Toraja had converted to Christianity. By 1965, the region was in a full-scale civil war, mainly because of the chaos of the post-colonial era and aforementioned religious conflict. All citizens of Indonesia were forced to become either Hindu, Buddhist, Christian or Muslim. Fitting in the belief system of the Toraja, in the eyes of the government, became a matter of national peace, tranquility and security.

Amongst the Toraja are followers of Islam with animist beliefs. Their belief system in regard to nature and animals is called “Aluk,” or “The Way,” and is officially recognized by the Indonesian government. Aluk is a complicated matter. The people of Toraja believe their ancestors came to Earth from heaven using a staircase. Aluk is interpreted by minaa (the name for Aluk priests) who synthesize the habits, mores, norms and laws associated with this form of spirituality. Agriculture (rice farming), funeral rights and socialization are all informed by Aluk.

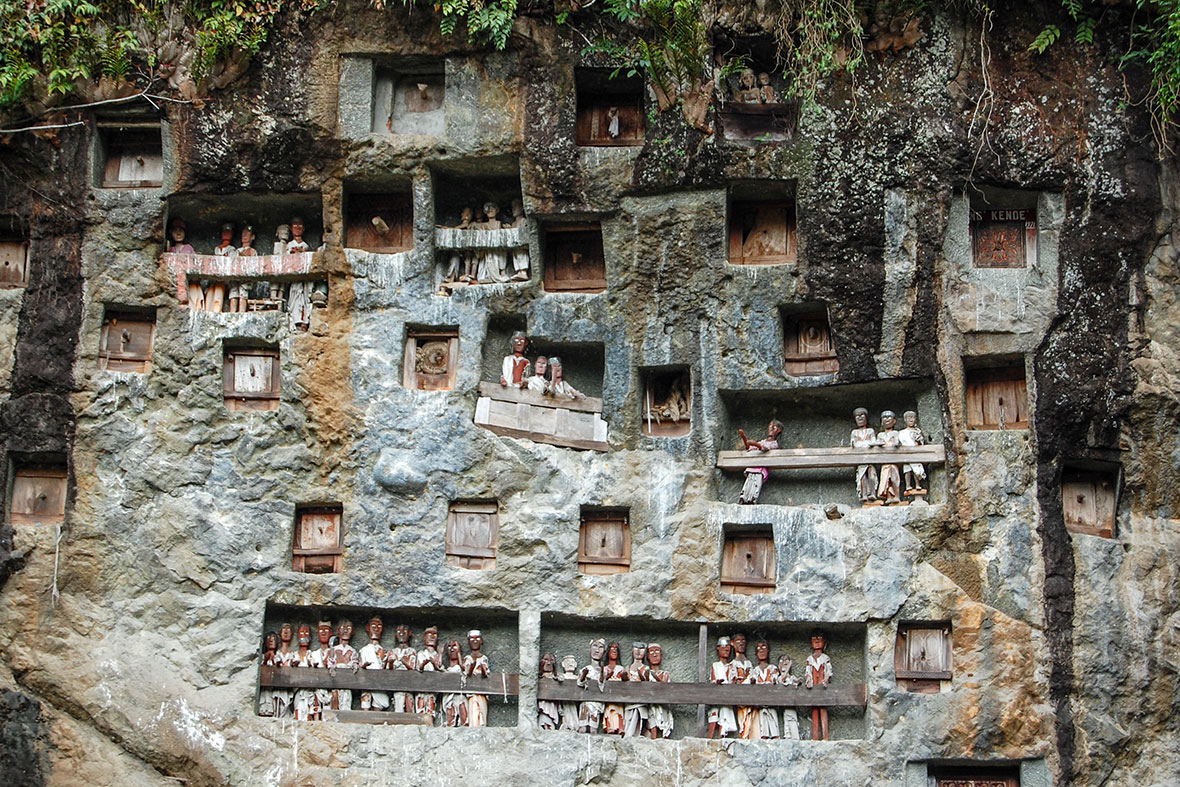

Toraja itself means in the basic form, “highlanders” or “people from the uplands.” The Torajans are well-known in the 21st century for their funeral ceremonies, their burial rituals, involving carving tombs on the sides of cliffs, their traditional longhouses or “tongkonan,” as well as their adherence to traditions, values for the past and belief in the afterlife. Funerals and death are central to the Toraja’s very existence. Having lived in relative obscurity until the 1970’s, it wasn’t until backpacking became trendy that they were discovered by the outside world.. Academics were soon to follow, studying and analyzing this unique culture.

I was drawn to discover more about Torajaland. I flew to Makassar from Bali and then drove approximately six hours north to Rantepao. The first four hours of the drive are pretty plain, and the traffic makes it a painful route. However, once we began our climb into the mountainous area approaching Torajaland, things started getting interesting. Not only was the scenery stunning, but I could see a very obvious cultural transition — the people were just different. South Sulawesi is dominated by the seafaring, Muslim Bugis people, whereas the Toraja were clearly a tribal, mountain culture with animist roots blended into Christianity. In other words, they really stand out. This is the world’s most populated Muslim nation, after all. The best hotel in Torajaland is the Heritage Toraja in Rantepao. It’s a surprisingly comfortable three-star property in a place where you’d expect nothing better than one or two stars, if any. I’m told this is because Toraja has been a popular destination with the European market for some time. Very few Americans ever come here, though.

Buffalo sacrifice is an important part of the funeral rituals in Torajaland, and the wealthier the family, the more buffalos must be slaughtered. Rich or poor, the cost of a funeral is usually a heavy burden — so much so that it often takes several years after someone dies before enough money is saved to buy the appropriate amount of buffalos for a funeral (buffalos are very expensive in Toraja- I saw one selling for US $20,000 in the local market, for example).

Funerals are usually the main highlight of a visit to Toraja. They are not somber affairs as they are in the West. Here,the whole village attends each funeral as a multi-day event. I was invited to sit with the family during the funeral’s burial day (luckily for me, I had missed them killing 20 buffaloes the day before). There were many rituals involving the coffin, which was stored in a special structure for two years (the deceased was a policeman from the village). All the buffaloes that had been sacrificed the day before were served to be eaten, and I was offered the opportunity to dine with the family. To be honest, the buffalo was pretty gamey, but I put on a brave face and ate what I was given, the whole time talking to the family members and learning about their customs. Everyone was really friendly.

After eating, they brought out the coffin. It was encased in heavy, elaborately–carved wood and as such, required more than a few people to carry it. Once brought out, the villagers situated nearby gathered in a big circle and started parading the coffin around, while dancing and jumping up and down. This went on for about 30 minutes, after which they carried the coffin out of the village for burial. One might think this was the beginning of the end, but it was merely the end of the beginning. The death rituals go on and on. We in the West cannot imagine this, but here, it’s a way of life.

Under “Aluk,” only nobles were entitled to death rituals and rites lasting for days on end, which were attended by thousands of guests. Outpourings of grief come in the form of songs, poems and even wailing. These people are only human, so of course death still brings plenty of sorrow. There are tears and sadness. Who can really get over the death of a loved one? The ceremonies of the Toraja are not held immediately after death as in Western culture. They can come months or even years later. To the Toraja, death is a slow process where you move towards the well of souls or “the afterlife,” called “Puya.” During this waiting time, the body is wrapped in cloth and kept beneath the longhouse. The Toraja believe that during this time, the soul of the deceased is haunts the longhouse and village. Only after the funeral rites have been completed will the soul depart for Puya.

Burial is carried out in a stone grave or in a regular cave. Wealthy people might get a cave carved out of a high cliff. It can take a long time to carve out a tomb. A wooden likeness of the departed known as a “Tau Tau” is placed upon the tomb as a look out. Some Tau Tau are hung on ropes, suspended from whatever can offer support. The most important facet of all is the Ma’Nene ritual, which takes place in August, when the dead bodies are exhumed, cleaned and washed, groomed (hair, nails and other factors) and then given a new set of burial clothes, before the mummies are paraded around the village. And if that isn’t enough to keep you up at night, then I don’t know what is.