As the US makes its final exit in Afghanistan, the Taliban is taking control. Once again, the region is being thrown further into darkness. This will undoubtedly have knock-on effects for Afghanistan’s neighbors, as well as one of the most treasured drives in Central Asia: the Pamir Highway.

Riding on the Pamir Highway through Tajikistan, staring over the border into Afghanistan, a shared people separated only by politics.

The Pamir Highway runs from the Tajikistan capital of Dushanbe to Osh in Kyrgyzstan, running around the Tajik national park and the Wakhan Corridor for more than 1,500 kilometers. Sections make up some of the most imposing roads in the region.

I spent four days along the border; Kalaikumb, Khorog, Ishkashim, and finally Langar. Throughout travelers can stare across the Panj (Pyandzh) River into Afghanistan’s snow-capped mountains and sleepy villages.

Scenes from across the Panj River. My first view of Afghanistan came as I approached Kalaikumb, with mud houses flanking the Panj, a peaceful scene.

For much of the entire journey, depending on whether or not you drive along the Gunt river, Afghanistan is a constant companion. For more than 500 kilometers, Afghanistan is an untouchable ornament to the Hindu Kush and the Pamirs.

Today, these winding mountain roads make up the second highest international highway in the world, but centuries ago, these jagged hills held the secrets of the Silk Road, a link with the West that changed so much in world history.

Memorable morning in Langar, with locals taking their sheep and goats to the river with the mountains of Afghanistan just a few feet away.

The region is Badakhshan ruled over by the “mirs of Badakhshan” who traced their ancestry back to Alexander the Great and his conquest of the East. Tajikistan, the armies of Kashgar, China, roving Khanates, and the disastrous Russian occupation. This world has changed hands dozens of times over the centuries, but the area has remained much the same. Borders change. Superpowers change. The people do not.

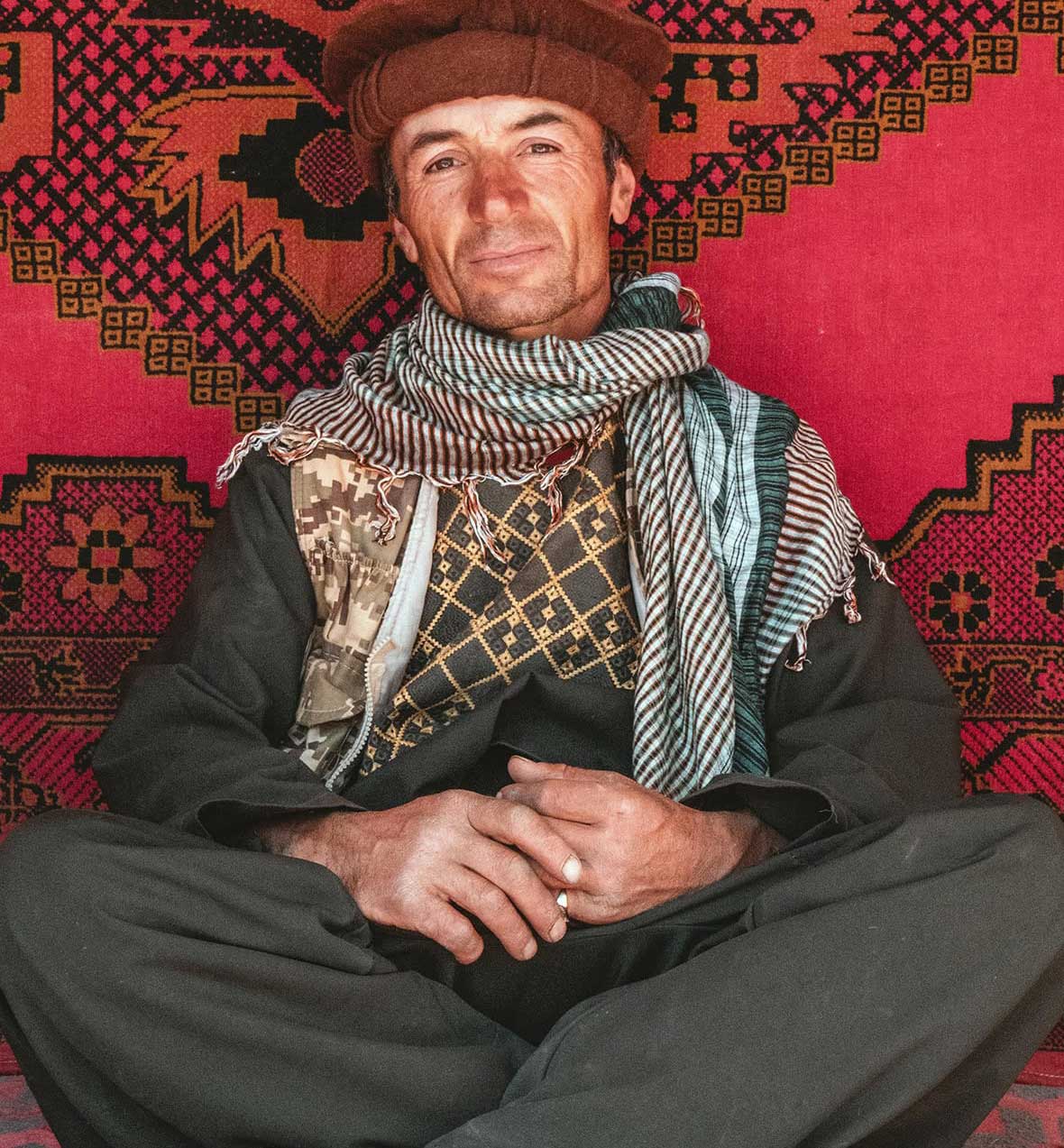

Afghan locals going about their daily lives fishing, washing clothes, and swimming in the river. On the approach to Langar, I met a man (top right) who had many family members on the Afghan side. He was dressed in Afghan clothing and took me on a short walk to his home for photos and a short chat.

In fact, I spoke to people on my journey who were born in Afghanistan and called Tajikistan home in the Wakhan Valley. Many on the Afghanistan side are ethnically Tajik; the border, for many, is easily (if not officially) crossed. And, in the case of the retreated Afghanistan soldiers, that imaginary line is crossed with great desperation.

Sign to Afghanistan.

I was never able to cross the river into Afghanistan, but the people I “met” seemed very friendly: lots of waves and the occasional thumbs up. We spent four days driving along the Afghanistan border. It would have been so easy to jump across to the other side, but obviously ill advised. There was a considerable military presence on the Tajik side to stop illicit trading or refugees.

A final glimpse into Afghanistan above Langar village on rock face with hundreds of ancient petroglyphs.

The road departs from Afghanistan at Langar village, a region of Afghanistan that was never controlled by the Taliban and the residents lived in relative peace apart from the occasional market attack. However, the new road that China has built in the region has made it more accessible than ever, and the Taliban have made their presence known.

The Pamir Highway, is surely one of the toughest landscapes in Central Asia. There is no telling how the US pullout from Afghanistan is going to affect the Pamir Highway, or indeed the entire region. My journey there in 2018 gave me a new understanding of the tenuous borders of one of the planet’s most restive regions — how beautiful and how fragile.