Four months before I crossed the border into Tachilek, Kuomintang-trained opium warlord Khun Sa massacred 90 government troops. Crossing that Mae Sai border into Myanmar, it was into his drug-fueled Shan State empire that I stepped in 1993.

With strict instructions against leaving the main road, the border authorities kept my passport, gave me a day pass, and told me that I’d be in big trouble if I didn’t return by sundown. I captured what I could.

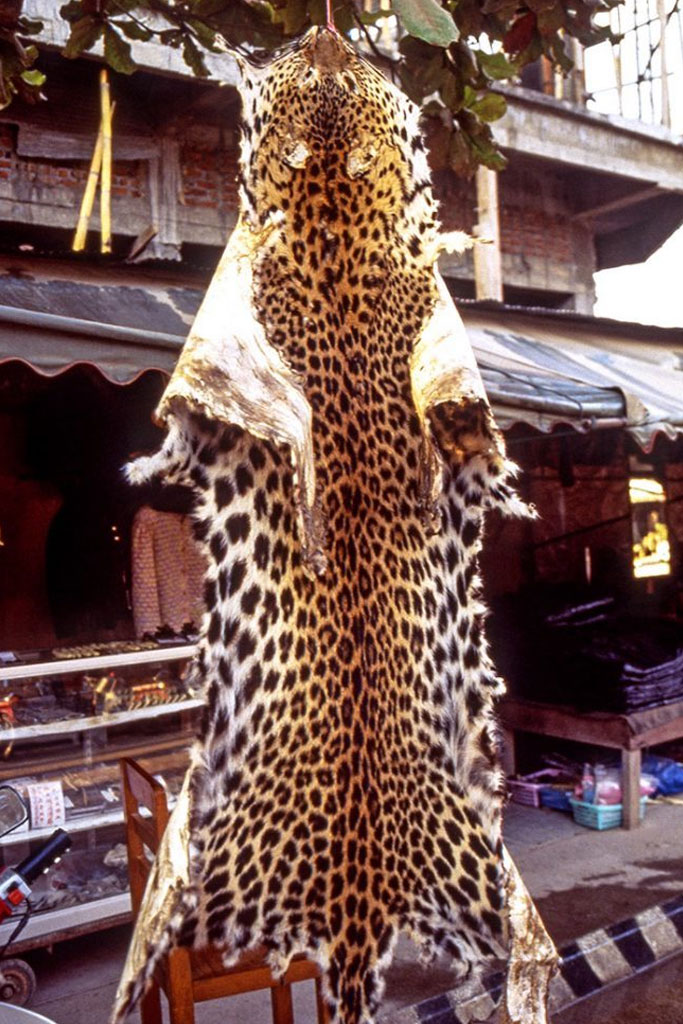

Crossing over into Tachilek, tribal people of the Shan State were found everywhere. The market – today replaced by bootleg Chinese DVDs and handbags – was filled with leopard pelts, tiger remains, and other rare animal parts. Khun Sa himself had once called Tachilek home, a lynchpin in the Golden Triangle. My inspiration for visiting this corner of the world was a photo spread in a Cathay Pacific magazine, featuring images of Keng Tung; I wouldn’t make it that far on my day pass, so I traveled to the side roads and villages on the way to Tarlay.

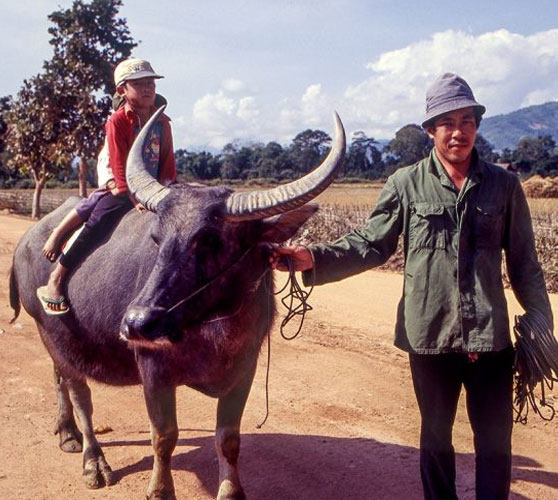

The few foreigners that would travel this newly-opened route would board a 4×4 to Keng Tung four hours away. Despite the severe warnings from the authorities, I was able to travel off the main road and meet with locals – soldiers, addicts, farmers – almost all of whom had never seen a Westerner before.

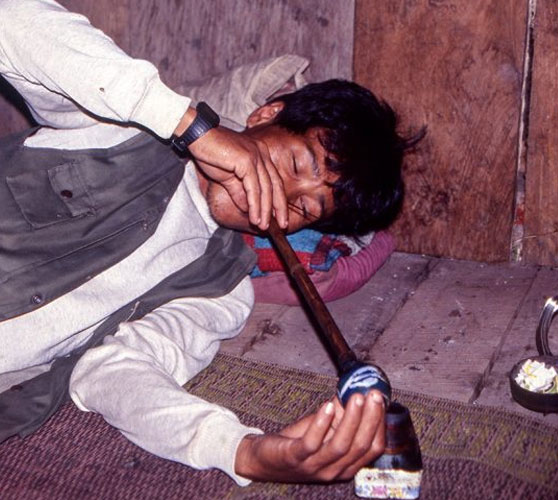

Opium and the Golden Triangle were synonymous with the Shan State, so when we traveled to an off-the-road village, we asked as tactfully as possible if there were any opium smokers to photograph. They took me to see an Akha tribeswoman lying down and smoking opium; her face was oily and she looked at me and smiled. Indeed, tribespeople were found everywhere throughout my trip – Lahu, Akha, Kayin – living normally just outside the cities.

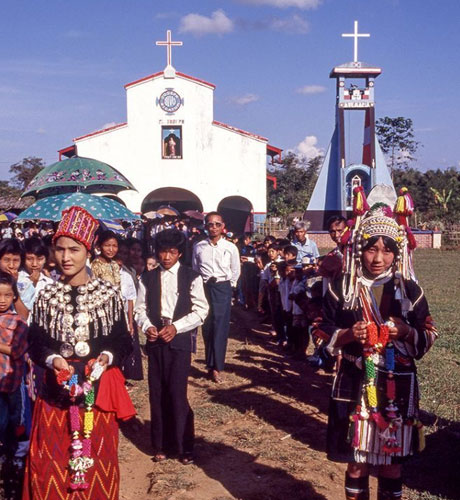

In Tarlay, the furthest point I traveled, a street dentist operated a drill by riding a bicycle and an interviewee kept telling me about her daughter’s virginity, but what most stood out was a farcical incident at a local Christian church. As I approached, people smiled and welcomed me warmly into their congregation with songs and instruments. Rather than simple Christian charity, however, it turns out they had mistaken me for their new bishop – a man from Kachin State that arrived undoubtedly confused only five minutes later.

Traveling further into the Shan state, I met with men with traditional tattoos and farmers. Poppies grew quite openly off the streets. This Myanmar no longer exists.

Part of what made this daytrip so extraordinary was my guide, a polyglot and extremely knowledgeable. At a local restaurant, military personnel spoke quite openly about their behavior because they assumed my guide couldn’t speak their dialect. He did. They spoke openly about taking whatever food they wanted from local villages as well as the women. I wanted to take a picture of them, but my guide wisely advised against it.

We visited a school where the teachers spoke English – a remnant of the British Empire – and the children were delighted with our company. In many ways this newly opened border area was not unlike my later trips to North Korea: isolated, curious, and wary but friendly. The quarter of a century that has passed since then has changed much in Myanmar, but many of the photos I took could have been from 80 or 100 years previous.

Three months after my short trip across the border, Khun Sa declared himself President of an independent Shan State in Burma, and that border crossing, open for such a short time, closed again. Five months after that, fighting began in earnest, killing 400.

The bridge at Tachilek hasn’t changed much, but almost everything else has. Today no more opium grows openly. No more markets of animal parts. No more tribespeople living openly on the outside of the towns. The drug war died, but its towns still stand.

Once again, Myanmar finds itself at a crossroads. There is some solace in the proof of how much the country can change.