Imagine a peaceful Buddhist country bombed and taken over by a hyper-militarized Maoist agrarian nexus. Picture all the people donning black pajamas, herded into the cities and then sent out to work in rice fields around the country. Next, imagine that 25% of the nation’s eight million people were killed, often with carpentry tools, after being tortured in the worst manner possible. Tragically, this was a reality in Cambodia, and today it’s possible to visit where these terrible tragedies occurred, in Phnom Penh’s “Killing Fields.” These horrendous events transpired in 1975 after the American pullout from Vietnam, and continued until April of 1979, when Vietnam invaded Cambodia to overthrow the Khmer Rouge, who were responsible for the atrocities.

On a recent visit to Phnom Penh, which I consider a surprisingly pleasant and enjoyable Asian city off the tourist trail, I visited the notorious Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, known as S-21, as well as the Killing Fields of Choeung Ek, to learn more about what happened there.

Visits to both of these sites proved to be sobering experiences. Most visitors to a new city are looking for fun, exciting activities and adventures, and these were neither of those things. However, I felt these places were important for me to see, as they are evidence of some of the greatest evil in history. I suppose visiting these places evokes a similar feeling to visiting a Nazi concentration camp like Auschwitz. But unlike the locations of some concentration camps, such as Dachau, which has been rebuilt, the Killing Fields have mostly remained as they were, in all their horror.

I went to S-21 first, once a high school in Phnom Penh. It is numbered because the Khmer Rouge had many such torture centers and the numbering system helped them keep track of which was where. The facility itself is fenced in, complete with barbed wire, surrounded by lovely trees with delicate white flowers growing outside: somehow they seem perfect and out of place all at the same time.

The name of the high school was Chao Ponhea Yat High School, named after a royal ancestor of King Norodom Sihanouk. What is especially shocking is realizing that this was real, that this actually happened while the rest of the world sat back and did nothing. I‘m glad I went to S-21 but I was also glad to have walked out of there. Between 17,000 and 20,000 people were imprisoned here, some because they spoke French, others because they wore glasses (interestingly, Pol Pot himself spoke French).

I was the only tourist at S-21 that day. In fact, apart from a man at the entrance, my guide and I were the only people there. And who would be surprised? After all, this is not a place you’d really want to be more than once. It felt like death’s door…and it once was. Yes, there are other torture centers around the world – ESMA, the Naval Mechanics School in Argentina comes to mind – but there’s nothing quite like this. The blood stains on the floors and the musty smell that percolated throughout the area helped me imagine the misery the prisoners must have endured in this place.

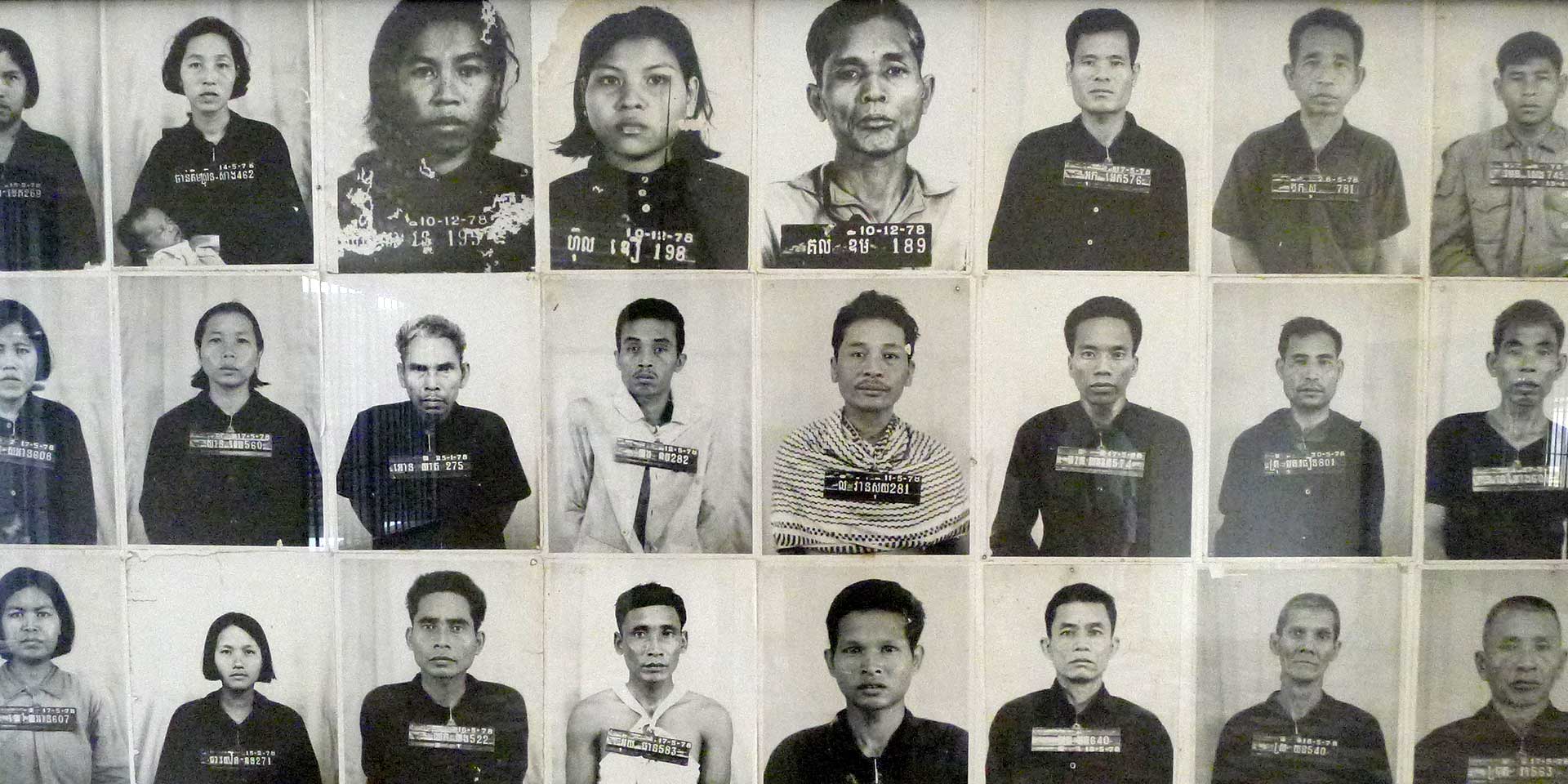

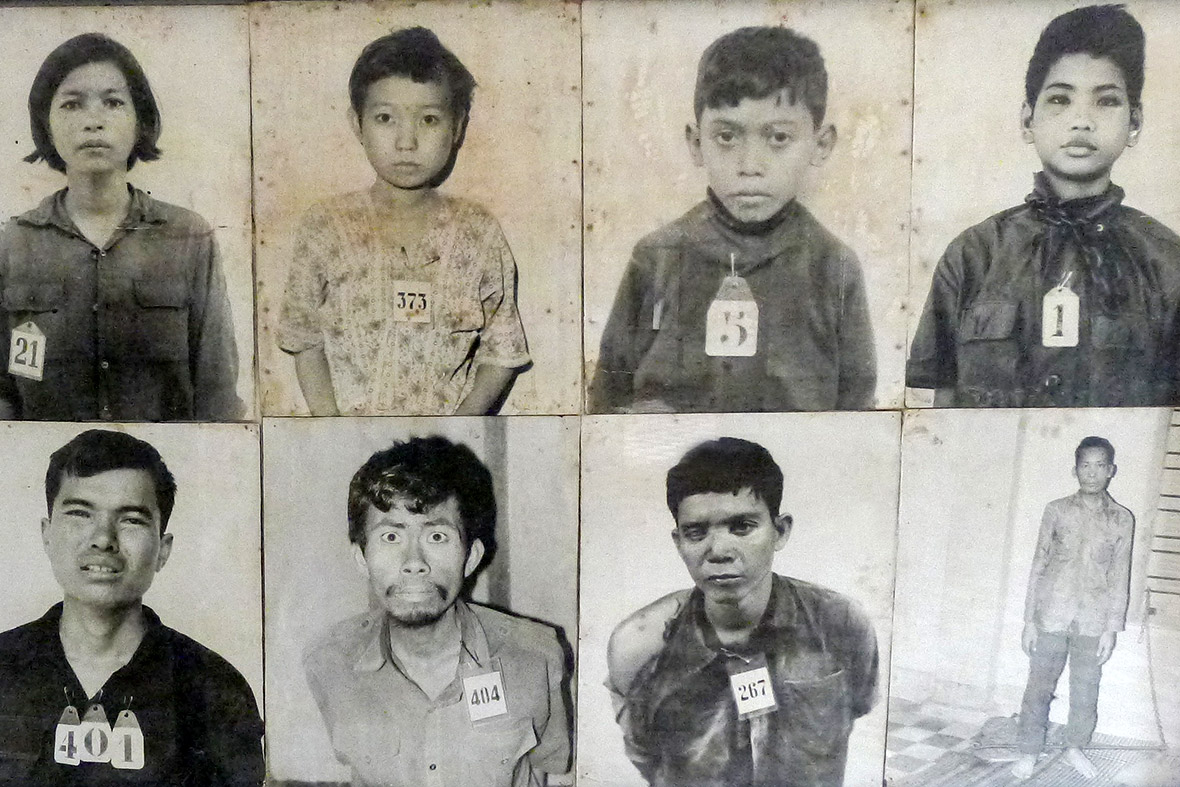

I didn’t have to imagine what the prisoners may have looked like: the Khmer Rouge made it easy, having taken photos of everyone they killed, which are now displayed throughout the complex. The faces of the women and children make the experience all the more haunting. You can see the absolute terror in their eyes. I will never forget it.

It is possible to meet a former prisoner that somehow survived S-21, and speak to this man through a translator, to learn first-hand what life was like under the Khmer Rouge. Of course, many people survived the Khmer Rouge and their “Year Zero;” but how many lived through S-21? This was a rare feat.

About 1,500 people were imprisoned here at any given time, but as the Vietnamese closed in on Phnom Penh, S-21 officials and lackeys began destroying documents, so the exact number of those tortured here may never be known. Only a few Khmer Rouge functionaries have ever been prosecuted in court. One of the main henchmen, “Duche”, shed some light on the events that transpired. The fact remains that in some extreme northern parts of Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge are still revered.

With S-21 behind me, I moved on to the Killing Fields of Cheung Ek — one of many, but the best-known of such places in Cambodia. My first thoughts were that the place had been made overly touristy. It wasn’t always this way: these days, there are food stalls, a museum, and a souvenir shop, but as recently as April of 1999 the road to the Killing Fields was unpaved, and it had an eerie feel of being untouched. There is a room where visitors are requested to watch a documentary about what happened in the Killing Fields, which is worth viewing as it provides context for what follows. I observed that there were more tourists here than at S-21.

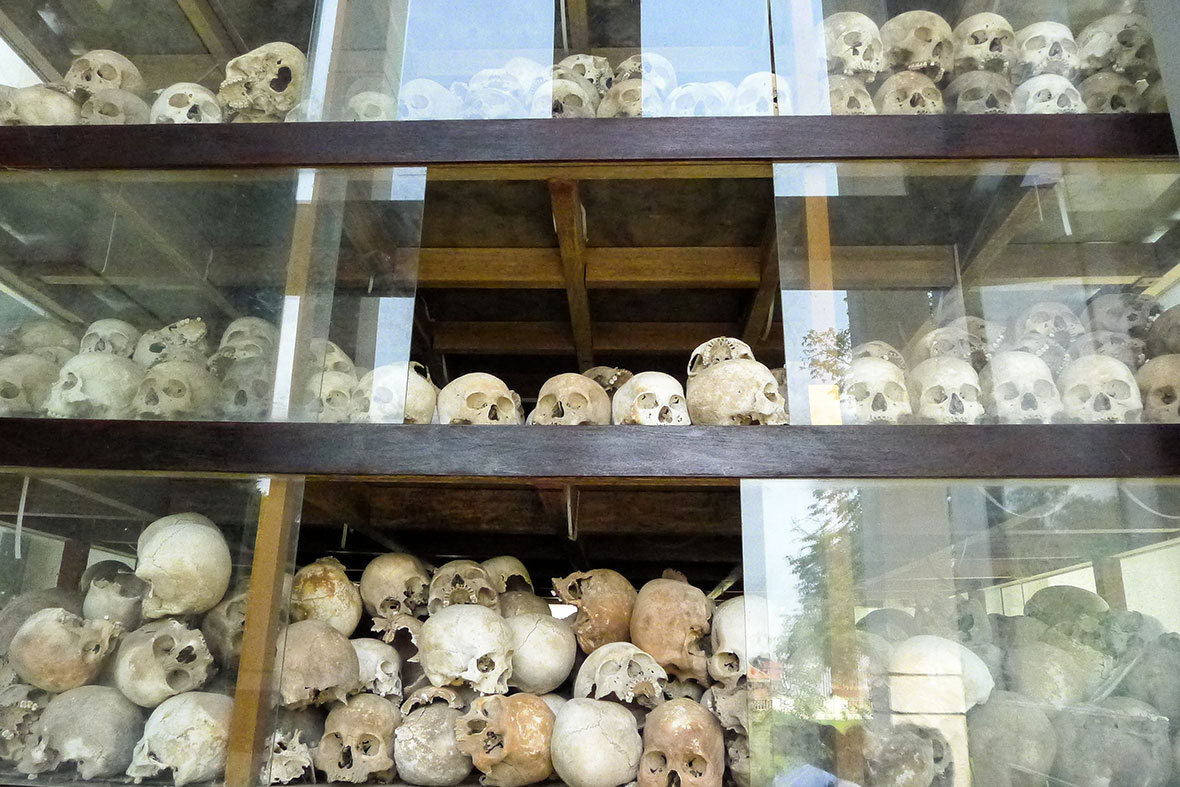

The “main attraction” is a horrifying sight: a memorial filled with more than 5,000 skulls of the victims that were killed amongst these fields. There are large pits, now grown over, into which bodies were dumped after execution. The Memorial Stupa is has a glass front, and inside, along with the skulls, are the implements used to execute the people: saws and hammers.

The Killing Fields are epic, ghastly and ghostly, but it is a place that I believe most Westerners should visit. There is a certain electrifying charge to Cambodia because of what went on during the Khmer Rouge years. Visiting the Killing Fields is no picnic, but they carry an air of grace and now, and even peace. And this is why we travel: to grow and learn and become more than we were before. The Killing Fields, while touching, saddening, and at times, overwhelming, has much to teach us on many levels about the human condition.