Flying over the vast, rolling steppes for three and a half hours without seeing anything so much as a village, let alone a city, is a powerful reminder that Mongolia is the most sparsely populated country on the planet.

Touching down in the predominantly Kazakh city of Bayan Olgii, in Mongolia’s westernmost Altai region, I was relieved to still have internet access on my phone and, as the small, unremarkable town of Bayan Olgii faded in the rearview of our 4×4, so too did my phone connection.

As we set up camp on the edge of the steppes outside the city, I found myself staring at the lights of Bayan Olgii in the distance and wondering why we didn’t simply spend our first night in the comfort of civilization with warm showers, electricity, and—most importantly—an internet connection. The strange truth is that I had crossed an invisible line, temporarily exchanging one form of civilization for another. The Altai demands that you cut the cord.

At the top, the five highest and most sacred peaks in Mongolia lay in front of me with the huge Potanin Glacier wrapping around them below

Traveling via Land Cruiser with a Kazakh guide and cook, and a Mongolian driver. My small tentipi had a foldable bed and was comfortable enough. Excited by the prospect of stunning scenery for miles in any direction, it became much colder than I had anticipated; I had the creeping feeling that my Mongolian Altai had its own plans for my journey.

The next morning we started the 10-hour drive to Altai Tavan Bogd National Park in Mongolia’s extreme west, bordering Russia and China. Bumping along dirt tracks, we passed Kazakh nomads and their grazing herds of yaks and goats and little else. The driver used the mountains as his compass.

Late in the afternoon we reached the entrance to the national park and continued off-road for another rugged hour. At the top the five highest and most sacred peaks in Mongolia lay in front of me with the huge Potanin Glacier wrapping around them below. Keen as I was to remain, it became cold; snow began to fall.

We worked our way back to camp, but it was too cold to stay outdoors, so we found a friendly Kazakh man who let us stay in one of his empty gers. I would become very familiar with Kazakh gers (called “Kyiz ui” by the Kazakhs) over the following nights; they tend to be larger and much more elaborate than Mongolian gers, often decorated with felt, embroideries, and handmade carpets. We fired up the stove eagerly, happy to have some heat while we ate dinner and spent the night at 9,560 feet.

When I noticed a wolf pelt hanging on the wall of one of our gers, my host explained that he had killed the creature himself to protect his animals.

My travels over the next few days took me further and further away from modern life and deeper into wild nomadic territory, both geographically and culturally. As we drove through the scenery, we passed herds of camels, horses, and goats – sometimes numbering more than 50.

When I stopped to fly my drone over one large group, the camels looked up as if an alien was flying overhead and nervously ran away. Similarly, when we visited a woman milking her yaks, just the sight of us was enough to spook the animals. Snow leopards and wolves call these hills home, and when I noticed a wolf pelt hanging on the wall of one of our gers, my host explained that he had killed the creature himself to protect his animals.

Despite the underlying dangers of the land, I was amazed at the warmth and friendliness of the Mongolian nomads. Hospitality is so deeply ingrained in their culture that a complete stranger can just walk into their home, and they will happily greet them and serve warm milk and dried cheese, an experience repeated literally dozens of times over the course of my journey.

I handed him my GoPro, and he happily took off and herded for the next 15 minutes, filming all the while

We continued the long drive to Tsambagarav Uul – a beautiful mountain on the border of Bayan-Olgii and Khovd provinces. At an elevation of 13,757 feet, its twin peaks are always snow-capped and it has sacred significance to the people of the region, whose way of life differs vastly from ours. Among them, we met a Kazakh eagle hunter teaching his young son the ancient skill of fox hunting with their impressive bird, boasting a wingspan of nearly six feet.

Later, as we lazed around our camp waiting for ominous-looking clouds to clear, an old nomad came to visit us on horseback. As we spoke, we watched his 12-year-old grandson single-handedly round up two herds of goats. I handed him my GoPro, and he happily took off and herded for the next 15 minutes, filming all the while.

Cameras were my only technology, and one morning, so awaking on a morning too cold to sit around, I walked 1,000 feet up a nearby hill to about 10,200 feet. The wind blew hard, and grey clouds engulfed the snow-capped mountain in front of me. At the top was a small makeshift Ovoo (a shrine made of stones), and a strong emotion overcame me – that sense found after being cut off from the outside world, that realization of the great big planet under foot.

In Khovd province, near the base of Sair Mountain, the wind was ferocious, and the temperature even lower thanks to the nearby glacier. Once again, we were lucky enough to find a Kazakh nomad family who let us stay in their spare ger to stay warm. Our hosts brought us a local dish called beshbarmak, which consisted of horse meat, mutton, and “shelpek” – local flat pasta and potatoes. As we ate, a young boy walked by with his dombra, and we asked him to play a few songs. He was a beginner, but it was a fitting experience.

Adapting to the Mongolian diet was very much part of the adventure. Comprised largely of meat and dairy products, most food is produced during the summer months and stored for the inhospitable winters. Warm milk (called suutei tsai) is a staple and we joined the locals for up to five or six bowls per day: yak, camel, goat, or cow milk, depending on which animals they were herding. It always tasted good – sometimes sweet, other times salty – but the sheer volume began to wear me down. I probably drank more milk in a week than I normally do in five years.

Midway through our drive, an enormous storm descended on us, with rains so heavy that flash floods erupted in almost every direction

As the nomads all herd animals, there is dung almost everywhere. You step in it, you drive over it, and most importantly, you use it to keep warm. There are very few trees in western Mongolia, so dung is the primary source of fuel for cooking and heating. It’s collected and put out to dry in the sun before being stacked in the large piles you can see next to every home.

My trip was almost completely dung-fueled, and as the sun set and the cold crept in, I was very grateful for it.

The next leg of the journey was another long drive, first passing through the city of Khovd, where we bought supplies and then toward Altan Hokhii Mountain – several hours away along more rough dirt tracks. The terrain was different here though; we passed between multi-colored mountains, alongside lakes and areas of desert scrub, dotted with pretty yellow Caragana bushes.

Midway through our drive, an enormous storm descended on us, with rains so heavy that flash floods erupted in almost every direction. The rain turned into a hail storm, and the ground went completely white in a matter of minutes. As I marveled at the transformation of the scenery, I felt a pang for the hosts I had just left, whose dung would would be ruined by the rain.

Our 4×4 navigated through the water and we passed through vast grasslands that rolled on as far as the eye could see to arrive at our lodgings around 9pm. After several days of camping with no running water, this private luxury camp was a welcome sight indeed.

After a hearty meal in a heated dining tent, I retired to my ger for a night of comparable opulence, and the next morning I had my first shower for five days. The shower tent used boiled water in a bag connected to a shower head.

After breakfast, we set off to the highest hill to survey the area. It was very peaceful here and we stopped to enjoy the view. Two nomads noticed us and rode over to say hello. With so few other people around, the locals will always come and check you out if you stay in one place long enough.

I learned that Altan Hokhii is home to the Myangad Mongols – one of the west Mongol ethnic groups and historically renowned as horse trainers that migrate between the desert plateau and the high mountains. Later in the day, we came across a group of children playing outside a ger, and so stopped to have a look. Inside, a Mongolian woman was making alcohol from milk with her mother – the grandmother of the nine kids we saw playing.

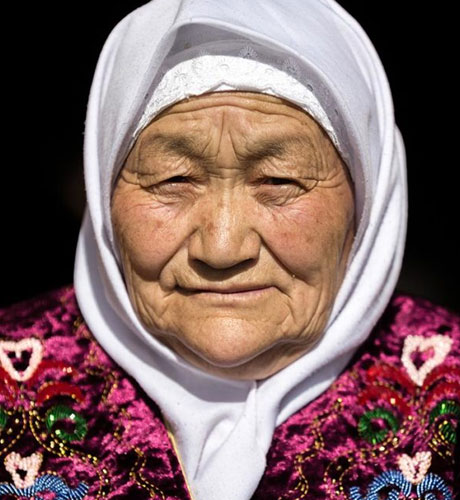

This fermented mare’s milk is known as airag – a favorite of the nomads. The grandmother was especially friendly, and as we chatted she explained that she was teaching all the families in the area about their local traditions, in the hope of preserving them as long as possible.

Reflecting on this during our final night in a ger camp, I felt lucky to have had the chance to immerse myself in the authentic nomadic lifestyle, even if for just a short time.

After my initial trepidation, the adventure had been a great reminder that good things rarely come easily, and experiences like this come at the cost of stepping out of your comfort zone and onto the steppes. The next day, as we arrived in Khovd on the way back to Ulaanbaatar, my phone started buzzing as the backlog of emails started pouring through. I was back on the grid.

But, I had met eagles and chatted with nomads. I had been warmed by dung and filmed with herders. The memories of my time spent in the Mongolian Altai mountains shall stay with me always.