Until 1992, Mustang was closed to the outside world. Even today, only a few thousand find their way to Upper Mustang each year. Other than the roads and altitude, one of my greatest difficulties came with finding somewhere to charge my gear. It’s vast, arid, and one of the few places left of Earth where one might truly escape to an authentic Tibetan enclave.

But all that could be changing.

Some of the biggest luxury hotel brands in the world are looking to put down stakes in this region, and there may not be a great deal of time left to see Upper Mustang as it is today – as it has been for hundreds of years.

The “feels like you’re traveling back in time” trope is overdone. Upper Mustang isn’t back in time. But it is isolated.

The airport at Jomsom is one of the most dangerous in the world. The flight from Pokhara is only 20 minutes, but the high mountains mean that the plane must angle its way through Kali Gandaki River gorge. The flight path is dangerous indeed – more dangerous if a go-around is required – but it does allow for views of Annapurna, Nilgiri Central, Dhaulagiri, and Tukuche.

There is a town in Jomsom where many choose to stay and acclimate after their flight in. For those heading further into Upper Mustang, it’s a last chance at reliable electricity, restaurants, and hotels. I, however, chose to be on my way. Up until a year ago, the next step on the journey was a difficult trek: one week in and one out. Today, however, there is a road, albeit a difficult one.

Clinging to cliffsides and rising up through mountain passes, the new road might barely be called a road at all. We moved at only a couple dozen miles an hour the entire time.

Our first stop was at Kagbeni, but not for sightseeing – for permits. Nepal may have started allowing travelers into Upper Mustang in 1992, but they’re still not very common. All travelers to Upper Mustang must apply for a permit and pay a fee of $500 per day.

The bumpy road continued on to Chuksang for lunch and continued on to Ghiling for a visit at a nearby monastery and to bed down for the evening. It must be said of Upper Mustang that – while it has some of the most spectacular scenery to be found anywhere in the Himalayas – it is not for beginner travelers.

I was there in April, and it was cold throughout. I wore as many layers as would fit on my body, but the dry, persistent cold seemed to work its way through everything. Heating is rare, and I shivered my way through dinner on that night in Ghiling. At an average height of 3,500 to 4,000 meters, cold and altitude sickness-induced headaches do not great travel companions make. The driving, too, was not without its challenges. We were stuck on one stretch of road for more than 30 minutes, digging our vehicle from the precarious road.

After a day of extremely bumpy roads and high altitudes, one might be yearning for high thread count sheets and a familiar meal, but travelers will find no such amenities in Ghiling – or, for that matter, Chele Samar, Syangmochen, or anywhere else along the way. The guest houses are modest, though fittingly so. The meek accommodations, however, are a toll worth paying for the culture, scenery, complete isolation, and the constant snow-capped majesty of the Annapurna range.

The next day we woke to drive to Lo Manthang – the walled city and kingdom to which most travelers to the region flock. It’s not uncommon for travelers to disembark at Josom and then hike their way to Lo Manthang over the course of week, but our drive there was – though difficult – far more preferable.

It was a long, tiring drive, and along the way we passed Tsarang and Ghar Gumba to visit the oldest monastery in Mustang. At Tsarang, I was able to fly my drone for awhile, which isn’t allowed, but the mountains and miles of emptiness didn’t seem to mind.

Finally, we continued onto Lo Manthang and checked in at Himalaya Guest house. The walled city is the former capital of the Kingdom of Lo that stretches back to 1380. Nepal annexed the kingdom in 1795, but the king retained his title until Nepal ordered the monarchy dissolved in 2008.

I was arriving only months after the last ruler of that isolated Buddhist kingdom, Jigme Dorje Palbar Bista, died. It was under these circumstances I was honored with a visit with the prince.

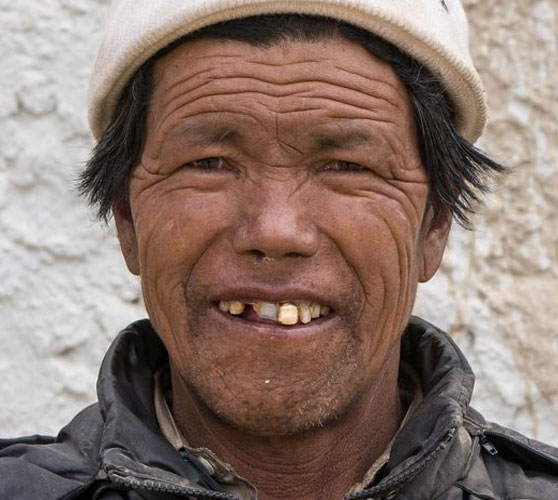

The people of Upper Mustang treat their history with reverence. Even after Nepal ended the monarchy in 2008, they still showed respect for their king. Largely unexposed to Westerners, the locals are friendly and happy to be photographed.

We were invited to the prince’s home and had tea. The royal line is now gone, but the prince – whose manner I found both warm and friendly – is now concentrated on saving the remaining royal properties of Upper Mustang that are in a state of disrepair. Today, the capital of that ancient Kingdom of Lo doesn’t look much like a seat of power, but in the nooks and crannies, the region still has a humble majesty.

During our time in Lo Manthang, we journeyed to one of the more curious sights in Upper Mustang: the Mustang caves. Found in Chhosar, there are a collection of 10,000 man-made caves dating back up to 3,000 years dug into the cliff and surrounding area. Paintings, sculptures, manuscripts and three-millennia-old human remains have been found in these curious caves – preserved by the cold and dry air. Some say these caves were for burial, others that they were for shelter, and evidence from the 15th century suggests these caves were used for meditation. Only a few of these caves are available for visiting.

Traveling in Upper Mustang is not cheap. It’s not easy. It’s not simple and it’s not comfortable. Upper Mustang is isolated by culture, by government order, and by geography. Princes of ancient kingdoms walk the walled cities, remains of the long dead rest in peace in caves from prehistory, and barely-cut roads wend through skies topped with mountains.

As the resorts roll in, some of the enchantment will fade, but, for now at least, Upper Mustang is a world of magic, mountain gods, and kings.