The number of tourists coming to Badakhshan is increasing,” says Odinamamadova Khinzobeg, a teacher in an Ishkashim; she speaks of this particular stop along the Pamir Highway in the Wakhan Valley in Tajikistan. Just over the raging Panj River is Afghanistan. “We hope that the quality of life will get better. It is better than last year.”

This teacher sits in the Wakhan Valley. Bounded by the Hindu Kush and Pamir mountains, the people here are known as the Wakhi. Found at a conjunction of Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and China, the history of the Wakhi people and the Wakhan Corridor is complex. The journey across the Pamir Highway long. It can be unpredictable, barren, and cold. In the faces of the Wakhi people, there is warmth.

Ishkashim starts the journey through what might be called the Wakhan Valley – keeping in mind the region extends to the Hindu Kush – all the way through to Langur. The Wakhan journey began in earnest with the ruins of the Khaakha Fortress, overlooking Afghanistan. This fortress, built in the 4th century, is said to have once had a bridge across the mighty Panj River. Today, it stands barren, visited by the few travelers with enough muster to make it this far on the Pamir Highway.

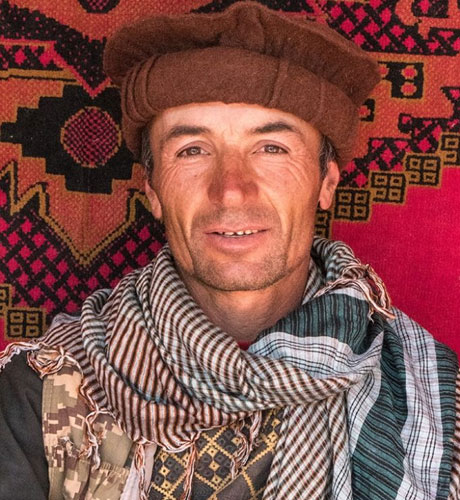

Here too we met an charismatic character: a Wakhi man dressed in the traditional attire of an Afghani; he invited us to his house to take photographs. It turns out that his family were in fact from Afghanistan. Indeed, the Badakhshan is mainly in Afghanistan; this far Dushanbe, borders mean little. The Wakhi man in Afghani dress did tricks with his massive goat – an animal almost as big as our host – tossing treats in the air for this beast to catch.

Later we moved on to Yamchun Fortress. From here, travelers can see into Afghanistan and all the way to the Hindu Kush; it is perhaps, one of the most iconic images of the Wakhan Valley. Built even earlier than the Khaakha Fortress, today, the bricks and masonry as still visible. In the 2nd century the Silk Road ran through this region, back when the Pamir Highway was for bandits and merchants. Modernity slowly ate away at the route, and when Chairman Mao declared the opening of New China, he closed the border and permanently ended the Silk Road trade from the Wakhan Corridor.

The Panj river cuts through the Wakan Valley: treacherous, and a natural element separating Afghanistan from Tajikistan. It’s not large, but it is powerful. The mysterious, dangerous reputation of Afghanistan adds a superficial element of jeopardy, and it would be a lie to say the region is entirely, 100 percent safe. But the Wakhan Valley is far removed from much of the cares of Central Asia.

Continuing on we pass the Bibi Fatima hot springs. Men visit the natural, steaming hot springs for a dip in the pale, blue waters that emanate from the nearby stalactite cave. The sight of 50 old, naked bathing men covered in powder is not a sight one forgets. The time there is separated by sex, a few hours for men, a few hours for women. Women go here to increase their fertility.

More tangible and living culture can be found in Yamg at the Museum of the Ismaili Sufi Mubarak Wakhani, dedicated to the beloved Mubarak-i Wakhani. “After the culture under the Soviet Union became so divided […] we wanted to show the foreign people the culture, the music,” says Ahmadbek Muborakqadamzoda, a descendant of Mubarak-i Wakhani, the famed sage, poet, and astronomer of Badakhshan region.

The museum is designed in the manner of a traditional Pamiri home, and a local was kind enough to play one of the instruments: an ornate wooden instrument with more than two dozen strings. It is played fast and with passion. The musician spoke at length about his art and the museum, a man desperately passionate about this curious valley in Central Asia.

Our fortuitous arrival in the Wakan Valley saw the locals in the thrall of local holiday celebrations. The people wore traditional Wakhi clothing, the women with their hair braided on both sides and embroidered hats. For most images of the Wakan Valley conjure scenes of stark, dry mountains. But, with the people, it is always colorful.

We came upon several celebrations, and in what was the highlight of a trip, we were invited to dance with the children at a celebration; members of our party were moved to tears at the hospitality and warmth of the people here. We were invited to the main festivities of another celebration by the organizer – largely on the novelty of having foreigners in attendance – to stand on the stadium stage to a crowd of a few hundred. There was dancing and joy, though it soon came to be suspected that we were causing a bit of a ruckus, taking away the focus of the main festivities.

In Vrang, we passed several Buddhist stuppas, and it surprises many to learn that this region has a deep Buddhist history. That said, there are those who argue that this structure was actually a Zoroastrian Fire Temple; today it is a small structure poking out from the snow-capped Pamir Mountains. Today the region is almost entirely Muslim, but evidence remains of this site’s importance along the Silk Road connecting East and West.

The final stop in the Wakhan Valley – but by no means the end of the Pamir Highway – is Langur. A rural collection of houses and livestock rather than a city. But it was in this city that I woke at 5am to to walk with the people as they took their cattle to the river and stare into the forbidden Afghanistan, a country that had followed us on this long winding road.

The friendliness of a people is often a cliche in travel writing, but in the case of the Wakhi people it happens to be true. They’re not just a people with a fascinating history, culture, and architecture; these are the caretakers of one Central Asia’s greatest treasures.